Doubles, Dyads, and Dualities: The Dynamic Factor of “Twoness” in

Visual Art Created by Willis “Bing” Davis

Bamidele Agbasegbe Demerson, Chief Curator

African American Museum and Library at Oakland

Oakland, California

African American Museum and Library at Oakland

Oakland, California

“One ever feels … two-ness …; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings.”

W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk, 1903

W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk, 1903

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the great scholar W.E.B. DuBois described the African American as “born with a veil … and gifted with second sight.” He identified this as a “peculiar sensation”—a “two-ness” or “double consciousness.” Indeed, a diachronic assessment of the African American, in DuBois’ words, revealed “the history of this strife.” While DuBois alluded to African Americans in general, his assessment is certainly applicable to Black visual artists and how this “strife” impacted decisions regarding their creative endeavors.

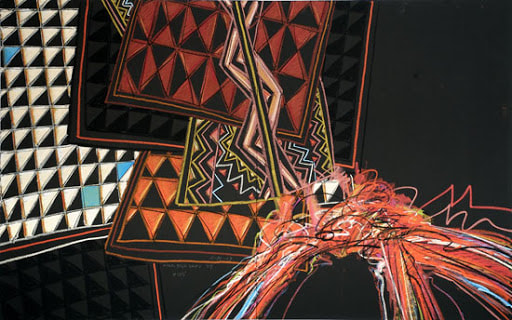

The resultant dissonance of “twoness” is indeed a dynamic consideration underlying the creative process employed by Willis “Bing” Davis. In fact, when he trained in the academy during the 1950s, modernism exercised a profound imprint on image making in Western societies. The modernists, of course, appropriated surface qualities from art made by the many inhabitants of planet earth held under the constraints of European colonialism. The peoples of Europe saw themselves as “advanced” and “civilized.” By contrast, the colonizers consigned the colonized to the categories of “tradition bound” and “primitive.” Western critics of Western artists therefore characterized their aesthetic appropriations as “modernist primitivism,” with all that his loaded concept came to denote and connote. Of course, while Davis explored, adapted, and innovated modernist idioms, his art consciously did not reify “modernist” thinking about the erstwhile “primitive.” As a Black artist—a descendant of the so-called “primitive” peoples of Africa—Davis, rather, envisioned a heuristic value in the social traditions from which African visual art emerged.

Visual art fabricated by Davis is rooted in an affirmation and valorization of his ancestral heritage—not a consigned Western notion of “primitivism.” He comments, “The rich … heritage of African art with its religious, social and magical substance is what I select as an aesthetic and historical link.” The artist also remarks, “I always like to acknowledge the African influence and the African American urban experience. I like to take traditional concepts and see how they fit in contemporary contexts.” Moreover, this remarkable visual artist expounds why. “When I look at the many life-sustaining rituals and ceremonies in which art was used in traditional African societies, I see many concepts and ideas that are valid today and worthy of preservation.” In Davis’ view, “The rediscovery [of this cultural heritage by] … African Americans would assist in the complex effort to bind us together as a people.”

The resultant dissonance of “twoness” is indeed a dynamic consideration underlying the creative process employed by Willis “Bing” Davis. In fact, when he trained in the academy during the 1950s, modernism exercised a profound imprint on image making in Western societies. The modernists, of course, appropriated surface qualities from art made by the many inhabitants of planet earth held under the constraints of European colonialism. The peoples of Europe saw themselves as “advanced” and “civilized.” By contrast, the colonizers consigned the colonized to the categories of “tradition bound” and “primitive.” Western critics of Western artists therefore characterized their aesthetic appropriations as “modernist primitivism,” with all that his loaded concept came to denote and connote. Of course, while Davis explored, adapted, and innovated modernist idioms, his art consciously did not reify “modernist” thinking about the erstwhile “primitive.” As a Black artist—a descendant of the so-called “primitive” peoples of Africa—Davis, rather, envisioned a heuristic value in the social traditions from which African visual art emerged.

Visual art fabricated by Davis is rooted in an affirmation and valorization of his ancestral heritage—not a consigned Western notion of “primitivism.” He comments, “The rich … heritage of African art with its religious, social and magical substance is what I select as an aesthetic and historical link.” The artist also remarks, “I always like to acknowledge the African influence and the African American urban experience. I like to take traditional concepts and see how they fit in contemporary contexts.” Moreover, this remarkable visual artist expounds why. “When I look at the many life-sustaining rituals and ceremonies in which art was used in traditional African societies, I see many concepts and ideas that are valid today and worthy of preservation.” In Davis’ view, “The rediscovery [of this cultural heritage by] … African Americans would assist in the complex effort to bind us together as a people.”

By pairing the heritage of African traditions with the needs of the African diaspora in North America, Davis has moved beyond the dissonance (or “strife” to use DuBois’s term) of being both an American modernist and a Black artist. Yet he continues to create with a distinctive “twoness” in his mindset. Sometimes this “twoness” draws inspiration from doubles or the specialness attributed to sets of ibeji (twins) among the Yoruba people. This theme is part of the abstracted twin wooden figures on Shrine to the Middle Passage, or the so-called Janus-faced images such as Brothers in Search of Self and Fertility Altar Piece in Nation Form. The twoness in Davis’ efforts is further realized in a loving dyad–a male and female couple—wearing African inspired masks in Ode to Two Black Dayton Poets. Equally significant, Davis presents dualities such as his fabricated guises bearing purposeful titles as Community Revitalization Dance Mask and Anti-Police Brutality Dance Mask. These titles imply the dualities present: the person donning the mask and the animating spirit force needed to bring about the desired action. The doubles, dyads, and dualities pervasive in Davis oeuvre is part of what he calls the “African influence” attributable to two dynamic phenomena extant in the Black community: the cultural memory of Africa and the cultural reclamation of Africa.

Office Phone: 513 932-1817

Email: [email protected]

Email: [email protected]

Wchs Office/Harmon MuseumTues - Sat: 10am - 4pm

Year Round |

1795 BEEDLE cABINPhone for hours

Year Round |