|

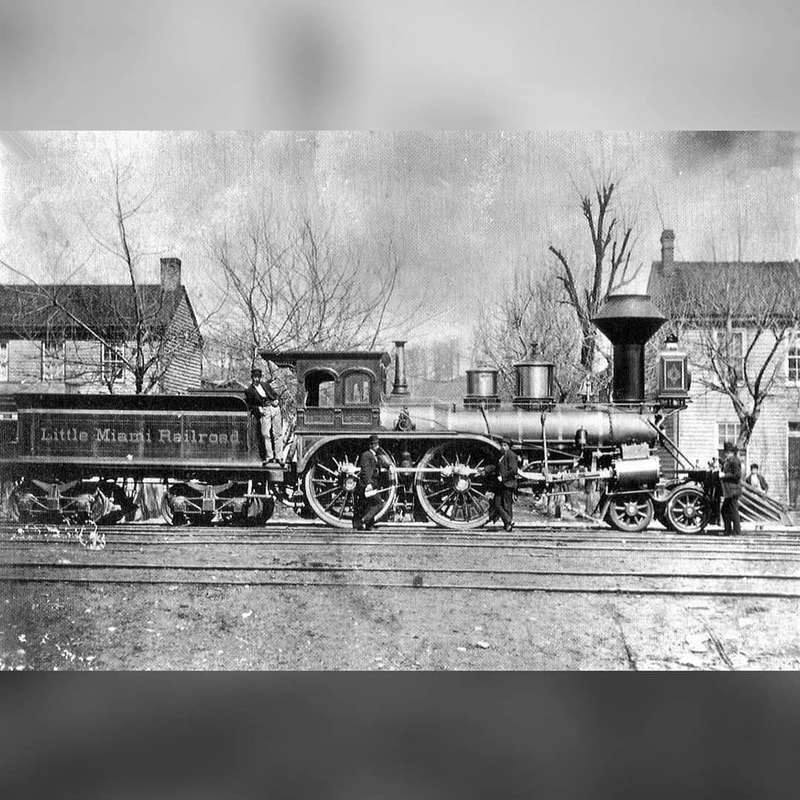

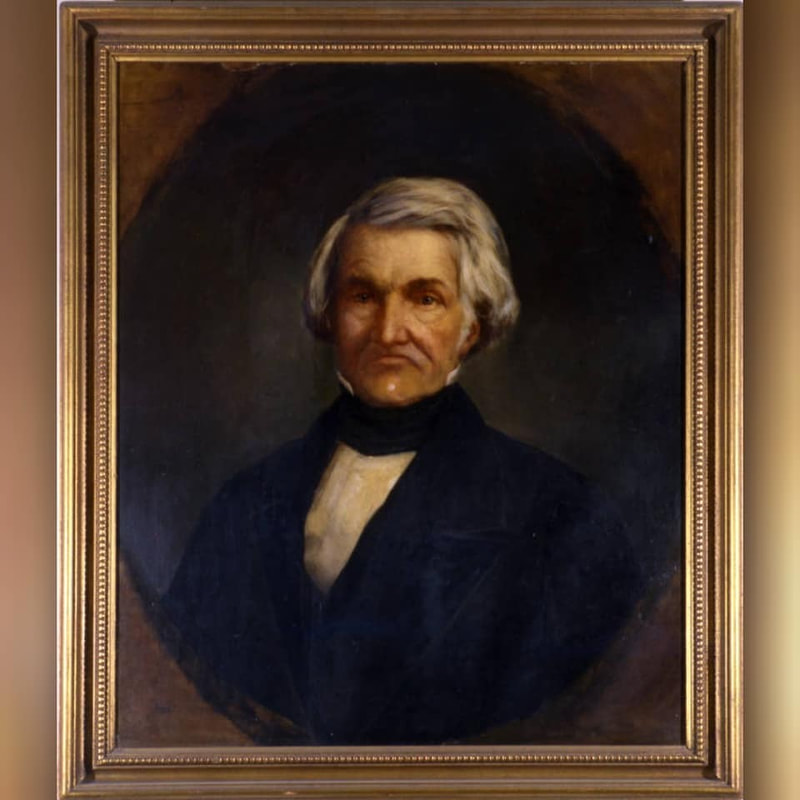

- from the desk of John Zimkus The town of Morrow was laid out in August, 1844 by William H. Clement, George Keck, and Clark Williams. All three men were involved with the Little Miami Railway, which was being built through the area at that time (more on that later). The town had 49 lots and was named after Warren Countian, Jeremiah Morrow (1771-1852). Morrow was the first president of the Little Miami Railway Company. He was previously Ohio’s first US congressman (and only for the first 10 years), as well as the 9th governor of the state. Morrow lived near Foster and his mill on the Little Miami River. 1. Morrow Train Depot

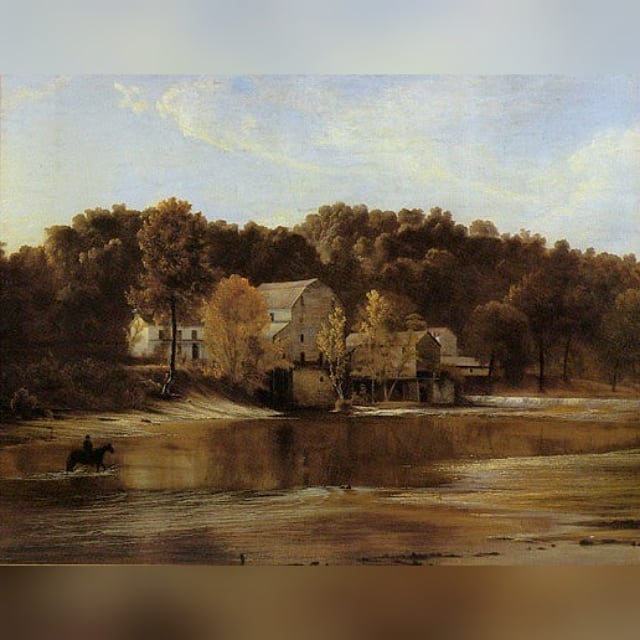

2. Little Miami Railway engine and coal car 3. Morrow Fire and Rescue ambulance (a Cadillac Miller-Meteor) photo circa early 1960s 4. Jeremiah Morrow - 1871 painting by John Henry Witt 5. Governor Morrow's Mill - 1869 oil on canvas painted by Godfrey Frankenstein For more on the history of Morrow (as well as some really great photos, including the one of the Cadillac Miller-Meteor), check out the Morrow Historical Society on Facebook or at www.LittleMiamiHistory.org

0 Comments

Donna Summers, Armstrong Gallery Curator  The Armstrong Gallery of Flight is now a part of the Ohio Aviation trail. When visiting the Armstrong Gallery of Flight, one of the first things guests notice is the mural that dominates the north wall. Created by Carol Ann Newsome, it depicts early Warren County aviators Clifford Harmon and Lincoln Beachey around 1909. Lebanon residents William and Clifford Harmon were fourth cousins to the Wright Brothers. Clifford achieved a number of aviation firsts, including being the first person to fly across Long Island Sound and the first aviator to carry a female passenger (his wife). In 1910, he became the sixth person in the U.S. to receive a pilot’s license. In 1926, Clifford sponsored the Harmon Trophy for outstanding aviators, aviatrix, and aeronauts (balloons or dirigibles). In 1969, a category for astronauts was added. Neil Armstrong received the prestigious award. Daredevil, stunt pilot and “America’s greatest aerial exhibitionist”, Lincoln Beachy, also grew up in Lebanon, Ohio. In 1900, when Beachy was 13, like the Wright Brothers, Lincoln and his brother Hillary opened a bicycle shop. Beachy earned his pilot’s license when he was 24; he was the 26th person to do so. He virtually invented aerobatics and was known as “The Man Who Owns the Sky.” Beachy often teamed up with race car driver, Barney Oldfield, and staged races. The two thrilled audiences around the country as Beachey’s bi-plane roared around a track in hot pursuit of Oldfield in his car. In one year alone, an estimated 17 million people, one-sixth of the U.S. population, saw Lincoln Beachey fly. In Warren County, new airports came from an unexpected source: farmers. Farmers nationwide saw the airplane as a new farm implement necessary to farm operations. Landings strips began to appear on farms nationwide. Aided by the Flying Farmers Association, local farmers changed the face of Warren County. Warren County Airport/John Lane Field began as a grass strip. John, an avid pilot, had courted his wife, Joann by flying her to a pasture near her home in Waynesville. After the two were married, they purchased a farm near Lebanon. They created an airstrip by mowing a north-south runway between their fields. As members of the Flying Farmers Association, the Lanes welcomed pilots from all over the United States to Warren County. In 1964, Ohio Governor James Rhodes decreed that there should be a paved runway in every county in the state. John Lane worked with Warren County officials to pave and light his airstrip. A second grass airstrip, the Red Stewart Airfield, was started in the 1950s. Red Stewart would fly his Piper Cub to work and land in the parking lot of Frigidaire Appliance factory in Dayton, Ohio. Eventually, when the Frigidaire plant manager told Stewart to stop flying his plane to work, Stewart quit his job and created an airfield on a 108-acre farm two-miles south of Waynesville, Ohio. It continues operations under the guidance of fourth generation family members. In 1960, a third farm airstrip was created south of Lebanon, Ohio. Brownies Airport, named after one of its owners, hosted a skydiving club and offered flying lessons. On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong, engineer, fighter pilot, test pilot, and Gemini and Apollo astronaut, stepped onto the moon’s surface. Armstrong’s moon walk lasted 2 hours and 13 minutes. Upon his return to earth, Armstrong stayed with NASA until 1971. Then he joined the faculty at the University of Cincinnati, School of Engineering and moved to Warren County. For 23 years, Warren County’s most famous resident, Neil Armstrong, and his wife, Jan, lived and raised their family on a farm less than two miles from downtown Lebanon. He was active in the community, serving on several boards, including the YMCA and United Way. Upon his passing, the Harmon Museum received many items from his estate including a gold plated frisbee from Whamo and a bronze bust of Armstrong. The Harmon Museum’s Armstrong Gallery of Flight has been accepted as a member of the Dayton, Ohio’s Historic Aviation Trail, “a non-profit corporation in partnership with the National Park Service, to promote Aviation Heritage in the Dayton region.”

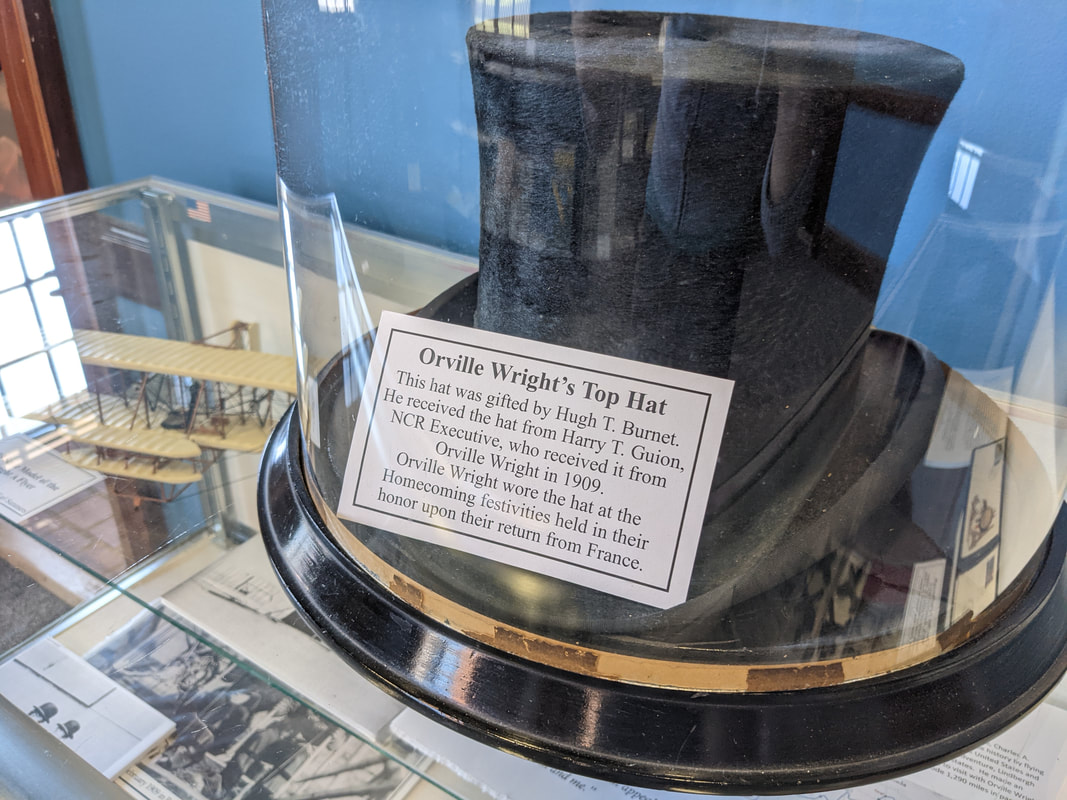

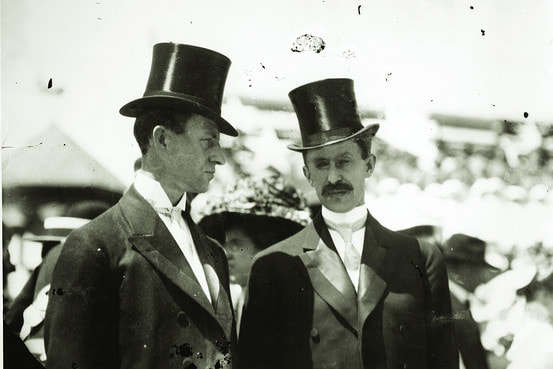

The Armstrong Gallery of Flight houses a collection of rare aviation related artifacts including Orval Wright’s top hat worn at the Wright Brothers’ Homecoming Celebration in June of 1909. Also on display are items gifted from Neil Armstrong and artifacts relating to the incredible legacy of Ohio’s Flying Farmers. Other sites on the historic Aviation Trail include The Wright Cycle Company, Carillon Historical Park, and the National Museum of the United States Air Force. For more information on the Armstrong Gallery of Flight, click here. It is open, along with the rest of Harmon Museum, from 10-4pm, Tuesday-Saturday. The Greater Loveland Historical Society's mission is "to collect, preserve and display historical information pertinent to the Greater Loveland, Ohio area, be regarded as a local authority on historical designation, serve as curator of locally significant art, and foster within our community an appreciation and curiosity regarding our area's past." "Through a combination of permanent exhibits, special presentations, and educational facilities," the Greater Loveland Historical Society "encourages guests to step back in time, discover the lives of Ohio's pioneers, explore Victorian-era comfort, and learn about the changes that time, innovation, and the industrial revolution brought to this early suburb and rural escape." The museum is open: March-December

Affiliate Member: Elizabeth Harvey Free Black School / Harveysburg Community Historical Society11/18/2023  Established in 1831 in Harveysburg, the Elizabeth Harvey Free Black School was the first free school for African American children in Ohio. In 1976, the Harveysburg Bicentennial Committee acquired the building and restored it. The building is now the home of the Harveysburg Community Historical Society and their community museum. In honor of Memorial Day, listen to the stories of those that made it home.

In Honor & Remembrance is a collection of conversations with over 35 veterans ranging in age from 27 to 96, covering wars and conflicts from World War II to Iraq and Afghanistan. One of the most historic buildings left in Warren County is the Greentree Tavern, located on the corner of St. Rt. 741 and Greentree Road. It was built in 1813 by Ichabod Corwin, the founder of Lebanon.

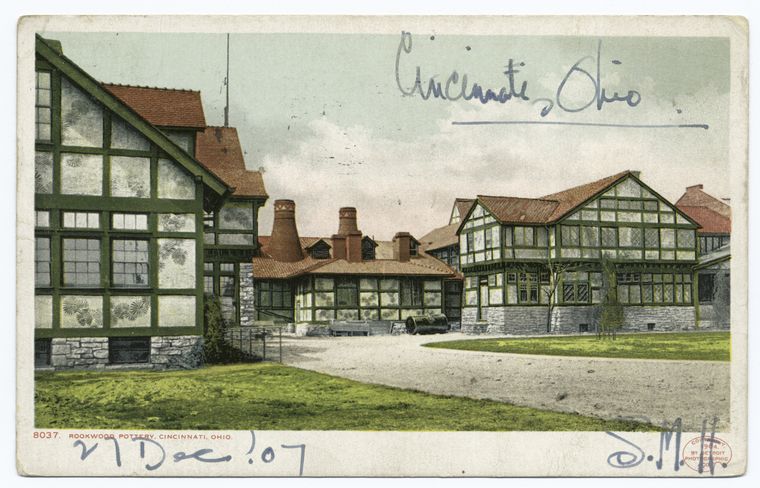

Rookwood Pottery is an American Art pottery company, located in Cincinnati, and founded in 1880. It was extremely popular until the Stock Market crash of 1929. and eventually closed in 1967. In 2004, it was revived, the new American Art pottery company taking the name and building on the old site.

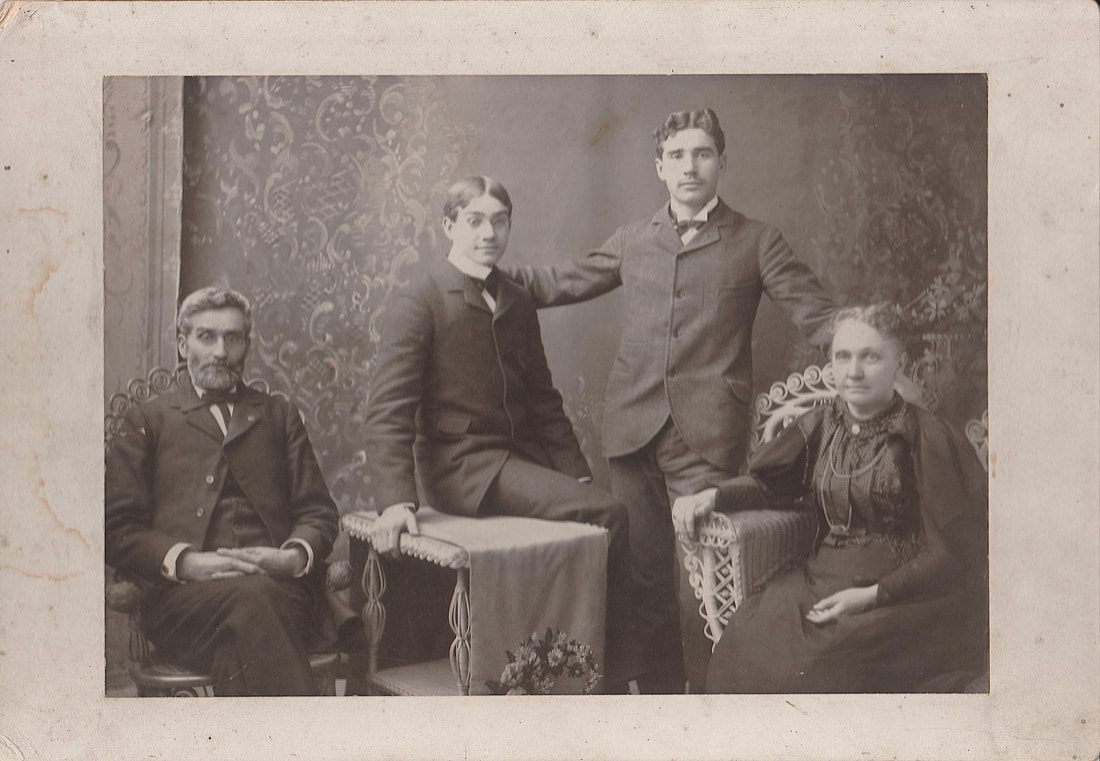

The Warren County Historical Society has an extensive collection of original Rookwood Pottery on display at Harmon Museum. A Trailblazing Lebanon Educator by John J. Zimkus, WCHS Historian and Education Director Louisa Jurey Wright is known by many as the first and, as of this writing, the only female superintendent in the history of the Lebanon public schools. She is also known for having an elementary school in town named after her in 1960. (It has since been demolished.) For over 140 years, her name has appeared on the list of superintendents who have guided the tax supported schools of Lebanon, Ohio since the early 1850s. During her lifetime Louisa Wright has been called "a woman of strong intellectual ability,” “a most excellent and highly educated lady,” and “a lady of superior culture and refinement and excellent Christian worth.” During the 1867-68 school year, however, when she was fulfilling the duties of the superintendent of schools in Lebanon, one thing she was never called was “superintendent.” Louisa Jurey was born on July 18, 1842, in sparsely populated Tymochtee Township, Wyandot County, Ohio. It was in the same rustic farm house in which her mother, Anna Drake Jurey, was born in 1819, some 23 years earlier. It was also the same house in which her mother married a Virginia-born farmer named John Jurey. Lou, as she was called by her family and friends, received her earliest education in a local country school. Like many successful students in the mid-1800s, once she reached the equivalent of an eighth grade education, she was hired to teach the younger children at her community school. The young and attractive Lou Jurey was always said to be optimistic. “She could see the bright side in the development of the human race,” it was observed years later. This was, and still is, a desirable attribute for someone who aspires to be an educator. With that goal in mind, in 1861, she went off to receive a formal education in Lebanon, Ohio. The village was located about 130 miles southwest of her home. The school she attended was the South-Western Normal School. It was founded only six years earlier in 1855 by Alfred Holbrook. In 1881, the school adopted the name by which it was best known, the National Normal University. By then it was the largest normal school, or teachers college, in Ohio. Louisa graduated in 1863. The Eighth Annual Closing Exercises of the South-Western Normal School took place on Thursday, August 3, 1863. Although there were 304 pupils enrolled in the school that year, many of them in the preparatory department, only seven graduated — two men and five women. As part of that day’s program, each of the seven graduates delivered an oration before Alfred Holbrook conferred upon them their diplomas. Louisa’s topic was “The Utility of Mathematics.” After graduation, she went off to teach in Paris, Illinois where her family had relocated. Paris is near the Indiana border, about 210 miles west of Lebanon, and about 12 miles north of the National Road, today’s US 40. After one year of teaching in Illinois she returned to Ohio. Once here, she taught for two years at the one room school house in Genntown, about 2 1/2 miles northeast of the center of Lebanon on the Lebanon & Waynesville Pike. In 1865, Louisa Jurey was hired to teach in the public schools of Lebanon Ohio. Besides her classroom duties, she was chosen to be the assistant to Lebanon School Superintendent Charles W. Kimball. She was paid $500 a year, which, adjusted for inflation, would be around $10,000 today. It was at this time the Lebanon school board became concerned that the district had no “regular course” of study for the “advanced department,” those students in the higher grades, and the primary department. As The Western Star, Lebanon’s weekly newspaper, reported years later, “Miss Jurey was chosen by the board to prepare a course of study for every department. The system prepared by her was afterwards adopted, with some modifications.” In the first decade of the 20th century, several letters from T. V. Blackman, from Pittsburg, Kansas, were published in The Western Star. He had worked at the newspaper almost 40 years earlier and was now a newspaperman in Kansas. Blackman wrote about his fond recollections of growing up in Lebanon. In one he explained, "My parents named me Theodore and this they corrupted to the name of Thode. When my playmates and school fellows in the old days wanted to ‘start something,’ they called me ‘Toad.’” In a letter published on May 7, 1908, he confessed that, while he was a student during the 1866-67 school year, he was one of a half dozen or so “young scoundrels [who] used to harass this good lady . . . Miss Lou Jurey.” In another letter published later that year, he exclaimed a “more mischievous gang never lived. I wonder if she has ever forgiven us for the many sorrows we caused her.” As a student, T. V. Blackman may well have had a crush on his young Lebanon Union School teacher, Miss Lou Jurey. She was only eight years older than her admiring pupil. His fond feelings for her may have lingered for several decades after leaving her classroom, for he mentioned her in several of his letters to The Western Star. Also in a 1908 published letter, Blackman recalled December 31, 1866, the day the county infirmary on S. East Street caught on fire. “I ran away from school to help haul the old side brake fire engine from the Washington Hall building to the scene,” he remembered. “We backed the engine down upon the pond by the ‘mad house’ and pumped water on the flames. The next morning I had to explain my absence to Miss Lou Jurey, my teacher.” He also told how, at a school “assembling,” late in the school year, it was announced, “Miss Jurey was to marry Captain Lot Wright.” Blackman went on, “After dinner [school lunch] all of us were in our seats demurely studying our lessons. On the blackboard on the east side of the room, was the admonition, ‘Remember Lot’s Wife,’ and when Miss Jurey saw it she was somewhat startled, as might be surmised. An attempt was made to find who had written it, but nothing was ever proven.” “Lot’s wife” is in reference to a passage in Genesis 19 of the Old Testament in the Bible. In it, Lot’s wife turned into a pillar of salt when she looked back upon the destruction of the wicked city of Sodom after being warned by two angels not to do so. (The exact words, “Remember Lot’s wife” were spoken by Jesus in Luke 17:32 in the New Testament.) Louisa Jurey, and her Lot, Captain Wright, were married in her mother’s home in Paris, Illinois on Wednesday evening, July 17, 1867. Lot Wright was born on February 16, 1839, near the small town of New Garden, in Columbiana County, in eastern Ohio and was of Quaker heritage. He began his formal education in Alliance, Ohio. In 1860, he became a student in the South-Western Normal School. He helped pay his way through school by teaching two winters in neighboring counties, one year in Butler County, and the other in Clinton County. It was while attending school in Lebanon, that Lot Wright first met his future bride, the lovely and intelligent Lou Jurey. In the summer of 1862, in the midst of the Civil War, 24-year-old Lot Wright enlisted as a private in Company I, 79th Regiment, Ohio Volunteer Infantry. In December 1863 he was promoted to sergeant. On June 22, 1864, he was severely wounded in the right leg in the Battle of Kolb’s Farm near Atlanta, Georgia. Six days later, on June 28, while still recovering in an Army hospital, he was promoted to the rank of captain and given the command of newly organized Company D, 100th Regiment, US Colored Troops. Because of his injuries, however, he was not able to join his unit until August. He commanded his men in the Battle of Nashville, where, on December 16, 1864, he was wounded again. According to an August 20, 1868 newspaper article, “a considerable portion of his right hand was shot off." He was mustered out of the army in August 1865. For the rest of his life, even though he would hold many important positions, he was often referred to as “Captain Wright.” During the summer of 1867, the public schools of Lebanon were showing some growing pains. A small article in the September 5, 1867 issue of The Western Star stated, “BABIES TO BE KEPT AT HOME. The primary department of the union school is so crowded that the board is compelled to refuse admission to all children under six years of age.” Another problem was that the longest serving Lebanon superintendent of schools up to that point, Charles W. Kimball, was in poor health. He had held that position for nine of the last 13 years, but could no longer continue. The school board turned to his assistant, the newly married Mrs. Louisa Wright, to take up his duties. She would be paid the identical amount per year that was given to Superintendent Kimball - $800. In today's money that would be about $16,000. She would now be in charge of the recently painted five-year-old Union School, located on what is now Pleasant Square Park; the separate school for Lebanon’s African American students, which was constructed in 1861 where New Street meets North Lane today; and all the students who attended the schools. The one major issue facing Louisa Wright as the superintendent of the Lebanon Public Schools was that, in the fall of 1867, there was no such position in the district as superintendent! How this was possible was explained in another brief article in that same September 5, 1867 issue of The Western Star. “Although the office of superintendent has been abolished Mrs. Lou Wright, principal of the high school, has general supervision over all the departments.” The official reason for not calling her “the superintendent” is not known. It may very well be that the prevailing thought among the men who made up the school board was that a woman, in the mid-19th century, should not hold such a position of authority. It might be seen as unseemly. The solution then, to them, could have been to let her act as the superintendent; pay her as if she was the superintendent; but not actually call her “the superintendent.” That way the fact that she was a “female” superintendent of schools would not draw attention. Whatever she was called, principal or superintendent, during the 1867-68 school year, Louisa Wright did have an achievement during her tenure in that role that no one had achieved before her. In 1868, under her guidance, Lebanon High School had its first three graduates, all female, - Ida Hardy, Ada Wood, and Minnie Van Harlingen. Lebanon High School would not have another graduate until 1872, four years later. In a June 24, 1915 article in The Western Star entitled “Lebanon's School Past and Present,” the comment is made, “The fact that [Louisa Wright] was offered a reappointment by the Board for the second year [as principal/“superintendent”] speaks for her success, but ill health required her to decline.” This statement may not be totally accurate. After going one year without technically having a superintendent, the Lebanon Board of Education decided it was time to have one once again. The Western Star on July 23, 1868 reported, “SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS The school board last week elected to the position of superintendent of the Lebanon Union School, for the ensuing year, W. H. Pabodie, for seven years Principal of one of these Cincinnati Public schools and more recently superintendent of the public schools of Peru, Ind. Mr. Pabodie is a graduate of Brown University. He was highly recommended to the board as a scholar and teacher and has had much experience in the management of graded schools. We commend the action of the board and securing for this position a classical scholar, as the superintendent will have charge of the High School, and all the branches necessary to fit a pupil for college can be pursued in that department.” William H. Pabodie was paid almost twice as much as Louisa Wright, $1,500 a year. He served as the Lebanon superintendent of schools until the summer of 1870. At almost the exact time in 1868 that Lebanon High School had its first graduates under Louisa Wright, Captain Lot Wright finished his education, and received a BA degree from the South-Western Normal School. Also in 1868, Lot Wright, a Republican, began his long political career when he was elected Warren County treasurer. He was reelected in 1870. In 1876, the voters of Warren County selected him to be their county clerk of courts, and then reelected him twice. In 1883, he was appointed United States Marshal for the Southern District of Ohio and served over two years in that capacity. Finally, in 1894, and in 1896, he was elected probate judge of Warren County. In the meantime in 1868, Louisa Jurey Wright, who left teaching after only five years in the classroom, turned her attentions to raising a family and supporting her husband. In a brief biography of “Judge Lot Wright” in the book History of the Republican Party in Ohio, published in 1898, it was said of Louisa Wright, “She has been to her husband a most able companion and helpmeet [a helpful partner] on life's journey, both in times of prosperity and adversity.” Lot and Lou had two sons, Willard Jurey Wright, born in 1875; and Raymond Garfield Wright, born in 1880. Raymond was named after Lot’s friend, and soon to be US President, James A. Garfield. Both boys attended Princeton University and became lawyers. Willard eventually was elected a Warren County common pleas court judge. Willard’s son, Louisa's grandson, was the famed mid-20th century industrial designer Russel Wright. His American Modern dinnerware was in production for two decades in the mid-20th century and grossed over $200 million in sales, earning it the title of the best-selling mass-produced dinnerware ever manufactured. For most of her adult life Louisa Wright was a devout and active member of the First Presbyterian Church in Lebanon. Beginning in the late 1880s, she was also was a member of the W. C. T. U., the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. In 1882, after living on the east side of Cherry Street between Main and Mulberry in Lebanon for years, Lot and Louisa Wright bought a newly constructed house on the northwest corner of Orchard and East Street – 214 E. Orchard Ave. It was in this house, in the Floraville neighborhood on a hill south of downtown Lebanon, that Lot and Louisa raised their two boys. It was also here where Lot Wright died a 6:30 p.m. on Thursday, February 22,1900.

The cause of his death was peritonitis brought on by a ruptured appendix. He had been confined to his home for only a few days. Judge Wright had retired from the probate court bench only two weeks prior to his death. The Western Star reported, “The funeral services were held on Sunday afternoon [February 25] in the Presbyterian Church with which the deceased had been so prominently identified.” Captain Lot Wright died six days after his 61st birthday. That was not the only tragedy to take place at the Wright home at 214 E. Orchard Avenue. On Wednesday, February 2, 1902, Louisa Wright and her son Willard where enjoying their noonday meal, when neighbors came rushing into their house. Unbeknownst to the Wrights, “fierce flames” were breaking through the roof of their home. The Western Star called it "the most disastrous fire which is visiting Lebanon for several years.” The origin of the blaze was in the attic and thought to be from the flue or pipes from the heater. It took over an hour to finally extinguish the blaze. According to the newspaper, controlling the fire was hampered by the fact "The fire companies [had] been allowed to disband during the past year and were not in good shape to fight an ugly fire, although the volunteers worked heroically.” The "richly furnished” Wright home was gutted and practically a total loss. The estimated damage amounted to $2336, approximately $79,000 in today’s money. Although the house at 214 E. Orchard Ave. was rebuilt, Louisa Wright is not believed to have lived there again. She instead made her home in a small house at 114 S. Cherry St. about two blocks away, near the Lebanon train station. She sold her Orchard Avenue house later in 1902. On March 14, 1903, Louisa Wright’s oldest son, Willard, married Harryet Crigler of Springfield, Ohio. In April 1904 their son Russel was born, followed two years later, in 1906, by their daughter Lizabeth Louisa, who was called “Libby Lou.” Willard built a large beautiful three-story Colonial Revival house at 238 Broadway in 1905. It was about two blocks west of the old Wright family home on Orchard Avenue on the Floraville Hill. There is no evidence to show that Louisa Wright moved into her son’s mansion. The local paper reported on Thursday, September 26, 1907, "Raymond Wright and mother left Monday for Seattle, Washington, where they will spend the winter in probably take up their future home.” Raymond, now a practicing attorney, would permanently settled in Seattle, over 2,300 miles away, and live there for over 60 years. About 6 months later, on March 5, 1908, The Western Star stated, "Mrs. Louisa J. Wright writes from Seattle, Washington, and renewing her subscription, ‘We do enjoy the paper, it is improving all the time.’” Louisa was ever the optimist. On February 11, 1909, the paper published one of the last letters sent from T. V. Blackman. He tells how he recently received a letter from Burwell Fox, one of the other “young scoundrels” who used to harass their teacher - Miss Jurey. Blackman states that Fox sent him current “Kodak” (photograph) of Mrs Lot Wright. The former “Toad” Blackman observed, "Like the rest, Mrs. Wright has had time whiten her hair, and add age to the once vigorous body; but the same sweet face is there, which we all loved, although we rascals who attended her school often caused it to wear a worried look.” On March 25, 1909, after spending a year and a half in Seattle, it was reported, “Mrs. Louisa J. Wright is expected home from Seattle, Washington next week.” The 1910 US Census records 67-year-old Louisa Wright living alone, and being the owner of one half of a duplex at 114 S. Cherry Street. A special gathering took place on Saturday, February 15, 1913, in Lebanon, Ohio. The group met in the “auditorium" of the five-year-old Lebanon National Bank building at 2 North Broadway. The occasion was the celebration of what would have been the 97th birthday of Alfred Holbrook, the beloved educator and founder of the National Normal University, the former South-Western Normal School. One of the speakers after the celebratory dinner was Mrs. Louisa Jurey Wright. Not only was 1913 the 97th anniversary of Professor Holbrook's birth (he had died in 1909), it was also the 50th anniversary of Louisa Jurey Wright graduating from the South-Western Normal School. The Western Star, in recording the event, said, “Mrs. Wright is a favorite with Normalites [students and graduates of the National Normal University], old and young, and can refer to the days gone by in a way that always adds merriment to the occasion.” Later than year, on October 5, 1913, at the first reunion of pupils and teachers of the Genntown School, Louisa Wright was one of several teachers who gave short speeches. Louisa Jurey Wright died on Monday, February 23, 1920, at the age of 77. She was living as a boarder at 217 W. Silver Street, between Water and Corwin streets. She died exactly 20 years and one day after the death of her beloved husband, Captain Lot Wright. Her funeral was held at the residence of her son, Judge Willard Wright, at 238 S. Broadway, at 2 o'clock on the afternoon of Wednesday, February 25, 1920. In the March 4, 1920 issue of The Western Star, the editor-in-chief, John Marshall Mulford, wrote an editorial entitled “Mrs. Louisa Wright.” It said in part: “Mrs. Wright and her husband were friends of the writer since his early boyhood, and many kind acts and helpful suggestions come to mind as we think of them. In their passing, two sincere friends are lost - rather, their familiar forms have passed from view, for friendship never dies, is never lost. . . .” Being a “Normalite" and a teacher, our earliest recollections, of Mrs. Wright is as an educator, and an ardent supporter of Dr. Holbrook's school of which she and her husband were graduates. . . As a teacher, and later as a patron of education, her voice always favored thoroughness in those branches of study she considered the formation of education, . . . “ . . . with her passing comes a recollection of her optimism, her faith, . . . and we but mourn her absence, realizing another good woman has entered Heaven.” Excerpt taken from:

The History of Warren County Ohio Part III. The History of Warren County by Josiah Morrow Chapter VIII. The Distinguished Dead This distinguished member of the bar was born at Lebanon December 17, 1807. His father, Enos Williams, was an early teacher of Warren County, and held several important civil offices, and among others, that of County Recorder for a period of fourteen years. John Milton received a good English education. In his boyhood, he assisted his father in the Recorder's office, and also wrote in the office of the Clerk of Court. His handwriting was legible, bold and rapid, and the training he received as a copyist at the court house was of benefit to him in his future profession. He studied law with Judge George J. Smith, and, before he had reached the age of twenty-four years, on the 7th of June, 1831, was admitted to the bar at a term of the Supreme Court held at Lebanon, with Judges Peter Hitchcock and Charles R. Sherman on the bench. Gen. Robert C. Schenck, who had completed his legal studies under Thomas Corwin, was admitted at the same time and place. Young Williams was poor, and was compelled to rely wholly on his own exertions. In after years, he wrote: "When I went out into the wide, wide world in business, on my own hook, I had two dilapidated shirts and a poor suit of clothes to match them. I opened my office in a cellar, with three musty old Ohio statutes, given me by my old father, which he had held as a public officer. This was my entire stock in trade." He soon acquired distinction at the bar. Not long after he began practice, he became Prosecuting Attorney —a position he held for twelve consecutive years. He was candid with his clients, and never misrepresented a case in consultation to encourage litigation. He charged lower fees for his services than other lawyers of the same rank. His popularity and personal influence with the masses were very great. For several years, he had a larger number of cases on the dockets of the courts than any other lawyer of the county, and was the attorney on one side of almost every important case. He could readily sway the minds of jurymen, and in the examination of witnesses he exhibited consummate skill. In 1850, he was elected a member of the convention which framed the second constitution of Ohio, and in 1857 he was elected Representative in the General Assembly of Ohio as an independent candidate over the regular Republican nominee. He was Major of the militia, and was uniformly known as Maj. Williams. In politics, he was a Whig, and afterward a Republican. The last years of the life of Maj. Williams are a sad history, over the details of which it is best that the mantle of oblivion should be drawn. Habits of intemperance separated him from his wife and family, and brought him to misery and want before he was yet old. He saw the extremes of life. He rose from poverty and obscurity to wealth and distinction; he sank again to obscurity and poverty. When possessed of considerable means, accumulated by his own energy and ability, he erected for his residence one of the finest mansions which had, up to that time, been constructed in the county; he died without a home. When the legal proceedings were commenced which took from him the ownership and control of his property, he wrote and read in the court in which he had practiced with eminent success: "God help me! I am a miserable and ruined man! Let the curtains of oblivion rest over the whole affair until that great day when all things shall be brought into judgment." He died July 21, 1871, aged sixty-four years, and was buried in the Lebanon Cemetery. Samuel Robert Bailey (1847-1906) Around 145 years ago, Bailey was the first African-American teacher and principal in the public schools of Lebanon, Ohio. Born a slave in northern Alabama, in 1863 during of the Civil War, he left the war torn South as a teenager and went to Sandusky, Ohio. Although illiterate, he saved enough money working to enter Wilberforce University. Seven years later he graduated. In 1876, He was hired to teach in the “colored” school, or African Union School, as it was sometimes called, in Lebanon. Paid as much or more than most of the district’s 9 teachers, around 1879, he was designated “principal of the colored school” and overlooked a staff of one other Black teacher. In 1883, he became the principal of the Lincoln “colored” School in Kansas City, Missouri. When he left Lebanon, The Western Star newspaper proclaimed, “Mr. Bailey is an intelligent colored gentleman, fully competent, to discharge the duties to the high position to which he has ascended. He was a good citizen and we wish him success in his home in the West.”

Written by John Zimkus A portion of this article was published in the November, 2021 issue of the Medallion, our membership newsletter. If you'd like to receive the Medallion and many other perks (including discounts to events and free admission to all our properties) you can become a member here. WARREN COUNTY’S OLYMPIC GOLD

by John Zimkus, WCHS Historian/Education Director Warren County, Ohio made it's first mark in Olympics history with three gold medals in the 1904 St. Louis Olympics. The Modern day Olympics were eight years old at the time, and this was only the third time the revised international competition was held. The winner of the gold medals was Matilda Howell. Her sport was archery. Matilda Flora Scott was born on August 28, 1859, in Lebanon, Ohio. Called Lida by her family, she was the only daughter of Thomas and Amelia Scott. Her father was a merchant who grew up in Union Township, where his father had a successful wagon making business. Lida's mother was a member of the locally prominent Sausser family who were mostly merchants in Lebanon. Lida attended the Lebanon Union School, where Pleasant Square Park is today. By 1880, her family had move to Cincinnati. Lida became interested in archery around 1878 as a result of her reading a compilation of witty essays called The Witchery of Archery by Indiana-born poet, essayist, naturalist and archer, Maurice Thompson. It did not take Lida long to become extraordinarily proficient in archery. She won the Ohio State Archery Championship in 1881 and 1882. Also getting very involved in competitive archery at this time was her father, Thomas Scott. In the spring of 1883, Lida married Millard Cecil Howell a Norwood Ohio native. By trade he was a coffee broker. Together they would have three children. Millard Howell was also a competitive archer. It has been said that Lida Scott Howell “had one of the most incredible records ever to be recorded in archery (or for that matter in any other sport.)” Between 1883 and 1907, Lida shot in 20 National Championships, winning 17 of them. Her scores in the 1895 championship set records which were not broken until 1931 – 36 years later. Lida and Millard, won the National Archery Association's National Championships in 1899, the only time in the history of the association that husband and wife won both titles in the same year. Out of the nearly 100 sports at the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis Missouri, archery was the only event in which women were allowed to compete. The competition took place on September 19 and 20 and involved six contestants, five of whom were part of Ohio’s Cincinnati Archers Club. Lida Howell, at 45 years of age, was the nation’s undisputed top lady archer, and coasted to the gold medal in both the Double Columbia and Double National rounds. She also received a gold medal as part of the winning United States archery team. Also competing in the St. Louis Olympics in archery was her father, Thomas Foster Scott. He competed in the men's double American round and the men's double York round, but did not medal. He was 71 years and 260 days at the time, making him the oldest person known to compete in an archery event at the Olympics. Born in 1833, Scott was also the 3rd-born known Olympian of the modern era, and the 1st-born known US Olympian. Lida Scott Howell retired from national competition in 1907. She died on December 20, 1938, and is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati. Lida was inducted into the Archery Hall of Fame & Museum in 1975. In 1904 a reporter from the Cincinnati Times Star interviewed Lida Howell. When asked why she preferred archery over other sports, she replied, "Archery is a picturesque game, the range with its smooth green and distant glowing target with its gold and radiating red, blue, black, and white, the white-garbed players, with graceful big bows and flying arrows, makes a beautiful picture.” Adding to that beauty, no doubt, would be the privilege of watching the grace, form and extraordinary skill of an Olympic Champion archer like Warren County’s Lida Scott Howell. Marcus Mote, born on June 19, 1817 in Miami County, Ohio, was a self-taught artist who pursued a career in painting from his studio in Lebanon. He was very talented and was able to achieve great success throughout his lifetime. However, today he is not only known for his artistic ability, but also for his Quaker heritage. Even though Quakers were critical of art, Mote was able to harmonize his conservative culture with the progressive ideas of the 19th century in his creation of four panoramas during the 1850’s.

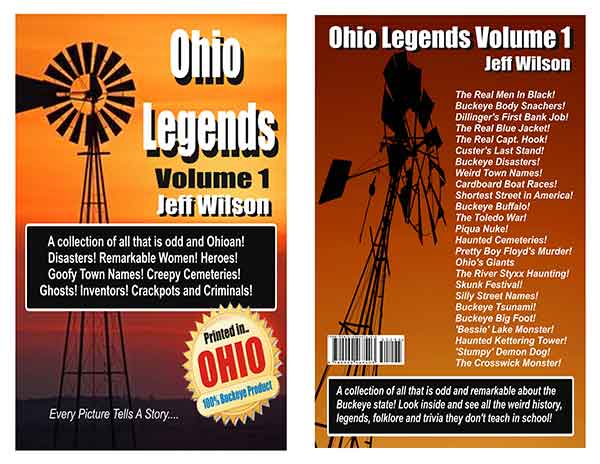

A panorama is a piece of artwork that is considered to be an ancestor of a modern day film. It consisted of a series of painted scenes, each about nine feet high and fifteen to sixteen feet wide, which together would create a story. The scenes would slowly rotate around a hidden mechanism, and as the scenes passed, the story was told by a narrator, called a professor. Marcus Mote’s first panorama debuted on May 9, 1853 in Lebanon Court House to a large audience. It was a recreation of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s famous anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Thus, it portrayed the story of Uncle Tom, a slave, and the harsh reality of his life. Mote’s panorama was successful in staying true to the novel’s plot; however, his artistic talent truly exemplified the deep emotions felt by the characters. The panorama’s first public appearance was overshadowed by another panorama exhibit in the area, but it nevertheless received glowing critical reviews. Mote’s second panorama was based off of Milton’s poems Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained. These two poems are descriptions of the biblical story of the Garden of Eden. It premiered on October 14, 1853, about six months after the debut of his first panorama. It also received sterling reviews, especially for Mote’s portrayal of the lush Garden of Eden. The third panorama, titled the Geological History of the Course of Creation, was Mote’s largest. It was comprised of a total of forty scenes, which were painted on a total of six thousand square feet of canvas. It was inspired by the eternal beauty of Niagara Falls, and required him to do considerable research into geology and paleontology. This research allowed him to create what he believed to be a comprehensive history of the earth and the creation of mankind. Mote was commended for his ability to harmonize the biblical representation of creation and the version maintained by geologists. Its presentation included music directed by a man known as Professor Schuler, and the panorama was very well received by a large audience. Mote’s fourth and final panorama was a series of scenes promoting the virtues of temperance. For its debut, Mote hired Luximon Roy, an eccentric East Indian prince, to narrate the panorama as well as to share aspects of his culture. The enthusiastic audience considered by the painting as well as the lecture to be brilliant. This panorama was also at a later time narrated by the famous temperature lecturer M.M. Edwards of Cincinnati. The creation of these four panoramas was a major stepping stone for Mote’s career. The popularity that he attained by creating panoramas stayed with him as he moved on to portraiture and landscapes. Unfortunately, none of these four panoramas exist today. However, from the numerous glowing reviews and descriptions that do exist today, it is evident that he was very talented as well as beloved by the people of Lebanon. Written by Kaitlyn Barnes The very popular Jeff Wilson once again paid us a visit to discuss material covered in his books Ohio Legends and Ohio Legends Volume 2. Every page in his books has a short story with an original, expressive illustration drawn by Jeff that brings to life a bit of Buckeye trivia or an oddity about an Ohio inventor, ghost, visionary, hero, crackpot or criminal. Jeff will be showcasing a special “Librarian’s Edition” of his Ohio Legends series that features a “perfect bound” cover and includes many stories never published before.

Ohio Legends Volume 1 & 2 are available in the Museum Shop. Jeff Wilson is a free-lance cartoonist, writer and illustrator. A life-long resident of the Buckeye State, he lives in Vandalia, Ohio with his wife Patti and enjoys any good, goofy story about Ohio. |

AuthorVarious staff and volunteer writers. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Email: [email protected]

Wchs Office/Harmon MuseumTues - Sat: 10am - 4pm

Year Round |

1795 BEEDLE cABINPhone for hours

Year Round |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed