Michael the Archangel 1965 Robert Koepnick Plaster Maquette Gift of John Koepnick On display in Harmon Museum's Contemporary Art Gallery FUN FACT: Koepnick pioneered a new casting process for the final work. This aluminum sculpture was made for St. Michael’s Church in Houston, Texas and is over 30ft tall!

0 Comments

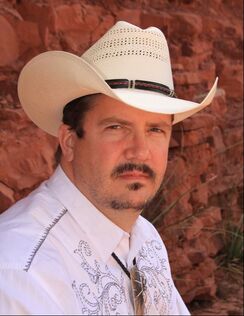

A native of Cincinnati, Angie (Tallarico) Meehan has been a life-long artist and painter. She began drawing at a very young age and pursued studies in art throughout elementary and high school, college and beyond. She has a degree in graphic design from UC’s college of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning and has studied painting with numerous accomplished contemporary artists. She is a signature member of the Woman’s Art Club of Cincinnati and associate member of Oil Painters of America (OPA). Angie’s work has been recognized and awarded throughout the years in both Club and juried shows. (bio supplied by the artist.) Connect with Angela on Facebook page. View Angela's work, and meet the artist, at the Opening Reception to her joint show with Scott Miller, Véjà Du- by Two, on August 11 at 6:30. Véjà Du- by Two will be on display at Harmon Museum July 28 - September 9.  A native of Lebanon, Ohio, Scott Miller is a product innovator, artist, and photographer. He holds a master’s degree in business and a bachelor’s degree in industrial design. Many products Scott has designed can be found in your home. Marshall Miller, Scott’s father, introduced Scott to photography as a child and his interest has continued to develop. Scott enjoys photo outings with Marshall, and together they have made numerous photography excursions. Scott’s photographic subject matter is primarily landscapes. These scenes are captured from his personal journeys, with images and compositions that unravel the complex majesty of this earth that we are so blessed to inhabit. Scott also enjoys woodworking as another artistic outlet. Scott’s professional design work can be found at the following locations: • Your home, Target, Walgreens, Wal-Mart, Costco, Kroger… • The Harmon Museum & Historical Society • The Cincinnati Art Museum • The Cleveland Art Museum • The Carnegie Institute of Art • The Chicago Athenaeum Museum His professional works have been honored by the following publications: • Six International “Good Design” awards • More than 100 design and mechanical patents. • Two Japan “Red Dot” awards • IDSA /Businessweek Magazine award • Fortune Magazine, Package Design Magazine, Dayton Daily News, and The Plain Dealer See more of Scotts Photography at his Online Gallery. (bio provided by the artists.) View Scott's work, and meet the artist, at the Opening Reception to his joint show with Angela Meehan, Véjà Du- by Two, on August 11 at 6:30. Véjà Du- by Two will be on display at Harmon Museum July 28 - September 9. John J. Zimkus, WCHS Historian/Education Director (featured in the July 2023 issue of the Medallion Newsletter) Mention the term “airship” and many people today may have no idea of what you are talking about. A few might know that you are referring to a dirigible, a lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power.

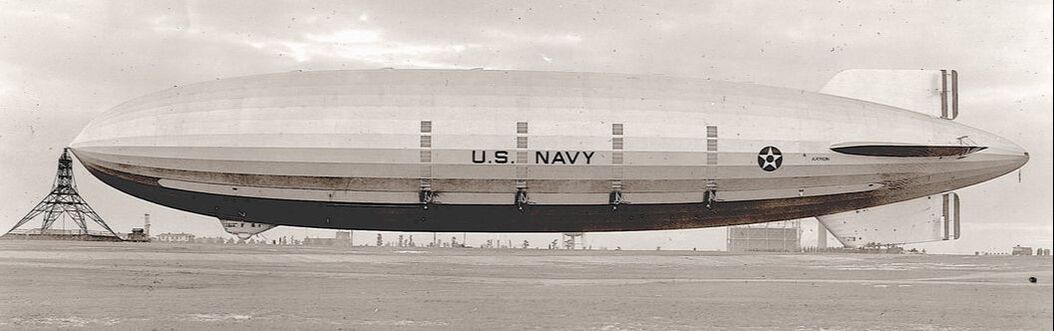

When you ask those familiar with the word “What was the world’s greatest airship disaster?” the vast majority of answers will probably be the horrendous explosion of the Hindenburg at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey on the evening of May 6, 1937. Out of the total number of 97 passengers and crew on board, 35 were killed along with one member of the ground crew. Anyone who has seen the famous newsreel footage of the Hindenburg going up in flames and crashing to the ground find it hard to forget. Nor can they forget radio announcer Herbert Morrison’s emotional cry of “Oh, the humanity!” as he witnessed the airship’s devastating conflagration. As memorable as the Hindenburg disaster was, it was not the world’s greatest airship disaster. That unfortunate distinction belongs to the all but forgotten US Navy airship, the USS Akron, nearly 4 years earlier. Ninety years ago, within the first hour of Tuesday morning, April 4, 1933, off the coast of New Jersey, the Akron went down into the Atlantic Ocean. It lost 73 of its 76 crew and passengers. Also perishing were two sailors who were attempting to rescue the survivors of the doomed airship. The “blimps” that can be seen flying over sporting events today are non-rigid airships. Typically the only solid parts on them are the passenger car (gondola) and the tail fins. Both the Hindenburg and the Akron were rigid airships. They had an outer structural framework that maintains the shape and carries all structural loads. The major difference between the Hindenburg and the Akron was the lifting gas. The Hindenburg used hydrogen. It has a high lifting capacity and was ready available but, as the Hindenburg proved in 1937, it is also highly flammable. The Akron used helium gas. It has almost the same lifting capacity as hydrogen and is not flammable, but is rare and relatively expensive. The Akron was the first of a class of two 6,500,000 cubic foot rigid airship built for the US Navy. Construction began in October 1929 by the Goodyear-Zeppelin Company at the Goodyear Airdock in Akron, Ohio. The USS Akron (ZRS-4) was christened on August 8, 1931, by first lady Lou Hoover, the wife of President Herbert Hoover. It was 785 feet long, about 20 feet shorter than the Hindenburg. It had a cruising speed of 55 knots (63 mph) and a maximum speed of 69 knots (79 mph). The USS Akron was a “flying aircraft carrier.” The heart of the ship, and said to be “her sole reason for existing,” was its airplane hangar and retrieval system. In May 1932, the Akron first tested its in-flight handling of the F9C Sparrowhawk, launching and capturing the small plane from its “trapeze”. This light biplane fighter was an example of a parasite fighter, a small airplane designed to be deployed from a larger aircraft such as an airship or bomber. The Akron could nominally hold five of the F9C Sparrowhawk, but practically it was limited to three. On the evening of April 3, 1933, the USS Akron departed the Lakehurst Naval Station at 7:28 p.m. on a mission to calibrate radio direction finding equipment along the coast of New England. A few hours after taking off it encountered unexpected severe weather just after crossing the east coast of New Jersey. The weather did not improve when the airship passed over Barnegat Light, New Jersey. Wind gusts of terrific force struck the airship's massive airframe. Around 12:30 a.m. on April 4, the Akron was caught by an updraft, which was followed almost immediately by a downdraft. Ultimately a violent gust tore away its lower rudder cables leaving the nose of the airship tilted upward between 12 degrees and 25 degrees. The crew was unaware of how close the tail of the airship was to the ocean surface because of its "nose up” position and the altitude indication was inaccurate. In that precarious position, and with the control gondola hundreds of feet high, her tail struck the ocean and its lower fin was torn off. The Akron then rapidly broke up and sank in the stormy Atlantic. Most of the 73 casualties met their death by drowning and hypothermia. Shockingly, the crew of the USS Akron had not been issued life jackets, and there had been no time to deploy the airship's one and only rubber life raft. The safety gear had been transferred to another airship and had not been replaced. The crash killed VIP passengers Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics who was often referred to as the "Father of Naval Aviation"; and Commander Fred T. Berry, the commanding officer of Naval Air Station at Lakehurst and its Rigid Airship Training & Experimental Squadron. The two were aboard the flight as observers. Another passenger on the dirigible that lost his life was Lt. Col. Alfred F. Masury of the US Army Reserve. Masury was vice president and chief engineer of the Mack Truck Company and was said to be “a fan of rigid airships.” It has been speculated that the Akron’s commanding officer, Captain Frank C. McCord may have commenced and continued the flight in the bad weather “in an attempt to impress them.” Capt. McCord also perished in the crash. Losing such leading proponents of rigid airships sounded the death knell of the US Navy’s program. President Franklin D. Roosevelt commented afterward, "The loss of the Akron with its crew of gallant officers and men is a national disaster. I grieve with the Nation and especially with the wives and families of the men who were lost. Ships can be replaced, but the Nation can ill afford to lose such men as Rear Admiral William A. Moffett and his shipmates who died with him upholding to the end the finest traditions of the United States Navy.” Of the 76 passengers and crew there were only three survivors: the USS Akron’s executive officer, and second in command, Lieutenant Commander Herbert V. Wiley; Boatswain's Mate Second Class Richard E. Deal, and Aviation Metalsmith Second Class Moody E. Erwin. In July 1934, Lieutenant Commander C. E. Rosendahl, after interviewing the survivors and examining the evidence, published the article “The Loss of the Akron.” In describing what happened on the dirigible in the early minutes of April 4,1933 he wrote, “Plunging suddenly into very turbulent air, the elevator man [controlling the altitude) reported the ship falling rapidly, the bow slightly down. His altimeter read 1,100 feet, he reported. Lieutenant Commander Wiley, second in command and a veteran of scores of scenes aloft in thousands of flying hours, jumped from his station near the directional control to the elevator man's assistance.” “The elevator man” Lt. Cdr. Herbert V. Wiley assisted was my uncle - 27 year-old Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Joseph J. Zimkus. On May 22, 1933, Lt. Cdr. Wiley gave testimony before a Joint Committee of the US Senate and House of Representatives. When asked who was in the control car of the USS Akron on that fateful morning of April 4, he answered, “Captain McCord, myself, officer of the deck, Lieutenant Redfield, elevator men Swidersky and Zimkus; and . . . the rudder man.” He was then asked if both Swidersky and Zimkus were “experienced men?” He replied, “Yes. Swidersky was the better elevator man. He was a better elevator man than Zimkus, but Zimkus has considerable experience. He was no rookie.” He was asked to explain “What makes a good elevator man?” He responded that it was one who “could keep the altitude with less motion of the ship than another man. That is, he reacts to his observation and instruments quicker than another.” When asked if he thought “a good enlisted elevator man is just as appropriately at that elevator control as an officer?” “Better, sir.” Wiley answered. He then explained its “because he gets some experience, and the training is considerable . . . We hold schools of instruction for the men . . . and try to give them enough of the background and knowledge of these things so that they can act intelligently and know what is happening. I think all of our elevator men without question were thoroughly conversant with all those things.” “You are perfectly satisfied with the system of having an enlisted man on the elevator wheel and rudder wheel?” he was asked. “Yes, sir.” was Wiley’s reply. Shortly before the crash, the Akron was flying blind because its radio had unusually heavy static brought on by the storm. "As they passed over the coast,” Lynwood Mark Rhodes in a 1966 American Legion Magazine article wrote, “elevator man Joe Zimkus saw lights below stretching away like a gleaming necklace toward the north. The problem was to identify them. Rapid changes in course had made it difficult to get an exact position fix. Were they from Atlantic City - or Coney Island? If Coney Island, that meant the Empire State Building loomed ahead somewhere in the shapeless, churning fog.” Rhodes went on to say,“Jagged streaks of lightening crinkles the control car walls when, pitching and tossing, first up, then down, the Akron hit storm center in a few minutes later. Zimkus had had considerable experience in such storms but it took all his strength just to hold the wheel steady. Suddenly violent turbulence hit the ship. The wheel spun from his grip, out of control, its handles racing like the hands of a clock gone berserk. ‘The ship’s falling!’ Zimkus yelled. [Coxswain]Toney Swidersky, standing behind him grabs hold of one of the spokes, bracing himself as best as he could. [Lt. Cdr.] Wiley dashed from across the car to help. . .” Within minutes all were in the ocean. “Water rushed through the open port window of the control car, which was listing to starboard,” wrote John Toland in his article on the Akron in the 1961 book Early Air Pioneers; 1865-1935. “The torrent picked up Wiley and carried him out the starboard window. He felt a mass of rubberized fabric on top of him and knew that he was being dragged down with the ship. He swam under water until his lungs seemed about to burst. Then he surfaced. Lightning flashed and, in the brief glow, he saw the dirigible, her bow pointed in the air, drifting away.” At 12:55 a.m., the now unconscious Lt. Cdr. Wiley was pulled from the water. The body of Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Joseph Zimkus was never found. Soon after her loss, Navy divers located the Akron’s wreckage about a hundred feet below the ocean surface east of Atlantic City, New Jersey. In June 2002, the research submarine NR-1 revisited the airship's crash site, where much of her collapsed framework remained somewhat visible in the murky water of the Continental Shelf. My Uncle Joe was born on June 10, 1905, in Stamford, Connecticut. He was the oldest of seven children to survive to adulthood of Lithuanian and Polish immigrants, Frank and Dominica Zimkus. He was not quite 11 years old when my father, Edward W. Zimkus, was born. Eddie, as dad was called, idolized his older brother Joe. Young Joe was apparently not much of a student. An article on him in the Stamford Advocate newspaper after the Akron disaster states that Joe enlisted in the Navy in 1920 “soon after running away from Rogers school in Stamford. His stature was greater that his years, and he was accepted.” (I attended the same Rogers Junior High School as a 9th grader the school year before my family moved to Ohio in the summer of 1964.) The 1920 US Census, taken on January 20 of that year, lists Joe Zimkus as being 14 and employed as a “bell boy” at a hotel in Stamford. By December 26, 1920, Joe, now 15, was in the US Navy. On that day, navy records show that he was admitted as a patient to the US Navy Hospital in Hampton Roads, Virginia with the notation, “Fracture simple left clavicle (fall).” Prior to his duty on the USS Akron, Joe was assigned to the USS Mahan (DD-102), a Wicket-Class destroyer that was converted to a light minelayer on July 17, 1920. In 1930, Joe married Naomi Miller. I don’t know much about my Aunt Naomi. I do know that she and Joe were married in Philadelphia, and that she was born in Pennsylvania. Census records state that Naomi was 12 years older than Joe. Joe Zimkus was counted twice in the 1930 US Census. On April 5, 1930, Joe, age 25, is listed as living with Naomi, age 37, at 128 Ninth Street in Philadelphia. The “head of house” is Joe’s “brother-in-law” Joseph Nelson. Ten days later, on April 15, 1930, Joe Zimkus is recorded again. His “street address” for this entry is the “USS Mahan - Navy Yard Philadelphia PA.” Uncle Joe is said to have “joined the Akron crew when the dirigible was commissioned.” That would put it in the summer of 1931. In April 1933, at the time of the Akron disaster, Joe and Naomi Zimkus were living in Whitesville, New Jersey about 5 miles from the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst. On April 6, 1933, two days after the disaster, The Western Star, the Lebanon, Ohio weekly newspaper, had a front page article whose headline read “Nation Shocked by Akron Crash.” The article recalled that on October 16, 1931, “Thousand of residence of the Miami Valley” watched “the ill-fated Akron, queen of the skies and pride of the Navy’s air service” fly over on its final test cruise. “Residents of Lebanon were able to secure a plain view of the Akron for several minutes as she appeared and gradually faded from sight in the western sky. Students in the local schools were given a brief recess in order to obtain a glimpse of the giant dirigible.” In 1948, back in Stamford, Connecticut, Ed Zimkus and his wife of three years, Betty, were expecting their second child. If it was to be a boy, Ed wanted to name it after his long lost big brother. That year, however, a cousin of Ed’s, who lived about 10 miles away, had a son and named him Joseph Zimkus. That infant, however, was not named after Ed’s brother Joe. To avoid confusion, when a boy was born in early March 1949, Ed and Betty Zimkus decided to still name the child after Joe but reversed the order of his first and middle names. That’s how I became John Joseph Zimkus. PHOTOS 1 The USS Akron (above) 2 A portion of the group photo of the crew of the USS Akron. Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Joseph Zimkus is believed to be the sailor on the floor in the middle. 3 A newspaper photo of Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Joseph Zimkus published after the disaster. 4 Uncle Joe’s US Navy duffle bag and footlocker, which are in my possession. Sylvia Outland, Art Curator

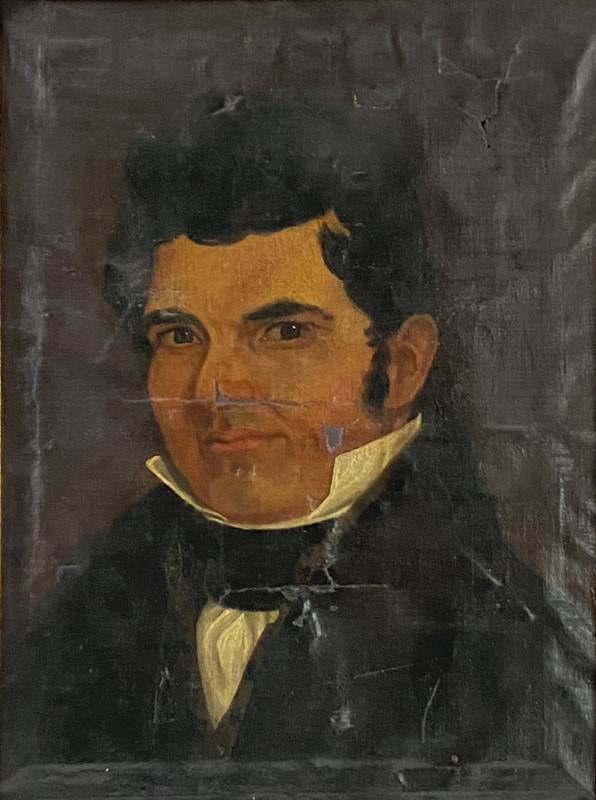

(featured in the July 2023 issue of the Medallion Newsletter) Earlier this year, the Ohio History Connection returned a portrait, to Harmon Museum, of James McDonald. As you can see from the before and after images, the portrait was in rough shape but has been restored by Old World Restorations of Cincinnati. It is not signed but we believe it can be attributed to Joseph Thoits Moore. Who was James Lawrence McDonald? Born in 1801 to a European father and a Choctaw mother in Mississippi, he was educated first in a nearby Quaker mission school. In 1813, at the age of twelve, his mother sent him to Baltimore to study under Phillip E. Thomas at the Quaker school there, who after a time, reached out to the Department of War, telling them of the possibility of using James to assist in the removal of Native Americans from tribal lands. Funded by the government, through the help of Secretary of War John C. Calhoon, McDonald continued his studies in Greek, Latin, philosophy, business, surveying and science. He was then pressured to pursue a degree in law, science or theology, but James wanted to return home to Choctaw territory to be close to his mother. However, in 1821 he began studying law under Ohio Supreme Court Justice John McLean, an early settler of Ridgeville, Warren County, Ohio and founder of The Western Star newspaper. James L. McDonald became the first Native American to be admitted to the Ohio bar in 1823. It is noted in the Western Star of July 12, 1823, “At the Supreme Court lately held at Dayton, Phineas Ross, Jesse Corwin, James L. McDonald and Thomas G Ward were severally admitted to practice a Counsellors, Solicitors and Attorneys in the Several Courts of Record in this state.” John C. Calhoon and Thomas McKenny tried to convince James to help assist in the removal of his native people. James refused and at that time returned to Choctaw territory becoming the first Choctaw lawyer and opponent of removal. In 1825 he was able to ensure the protection of mission schools, obtain high annuity payments and forgiveness of debts of the Choctaw. As an advocate of schooling, learning of social and cultural differences, and his experience of the harsh treatment he encountered during previous negotiations, James later came to believe that the only way for the Choctaw to survive was to agree to removal. In 1830 he signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. This treaty allowed those Choctaw who wished to, remain in Mississippi and become the first major non-European ethnic group to gain recognition as U. S. citizens. He stayed in Mississippi where he took his own life in 1831. Known for his Activism on behalf of the Choctaw Nation, McDonald’s work paved the way for future Native American leaders who were able to defend the rights of their territory using the American legal system. James Lawrence McDonald was an advocate and fighter for the rights and survival of his people and fought for them, their land and culture. His portrait is proudly displayed in the Harmon Museum. The portrait came to the Warren County Historical Society from Warren M. Miller of Hamilton, Ohio. He stated to Miriam Logan in a letter of February 1955: “Concerning the Indian painting which is in my possession, and the only one that I know of; it has never been photographed to my knowledge in my time…” “… It is very dark, and crudely patched in the region of the nose...” “You may tell Mrs. Phillips that I have seen to it in my will that it (the portrait) spends the remainder of its years in the Warren County Museum.”  1908 Buick Model D On display in Harmon Museum. Gift of the Ertle Family David Dunbar Buick, Walter Marrs and Eugene Richard started building the Model B automobile in Flint, Michigan in 1904. The Model D was the first full-sized Buick to join the smaller Model B in 1907. The Model D has a four-cylinder, 255.0 cubic inch T-head engine that was installed in the front with a rear-wheel drive and was one of the only cars with side valves that Buick made. The brakes on the Model D are mechanical with levers attached to the rear axel and drive shaft. FUN FACT: 1908 was the last year Buick used kerosene for their lamp headlights. |

AuthorVarious staff and volunteer writers. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Email: [email protected]

Wchs Office/Harmon MuseumTues - Sat: 10am - 4pm

Year Round |

1795 BEEDLE cABINPhone for hours

Year Round |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed