|

John J. Zimkus, WCHS Historian/Education Director (featured in the July 2023 issue of the Medallion Newsletter) Mention the term “airship” and many people today may have no idea of what you are talking about. A few might know that you are referring to a dirigible, a lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power.

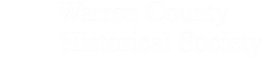

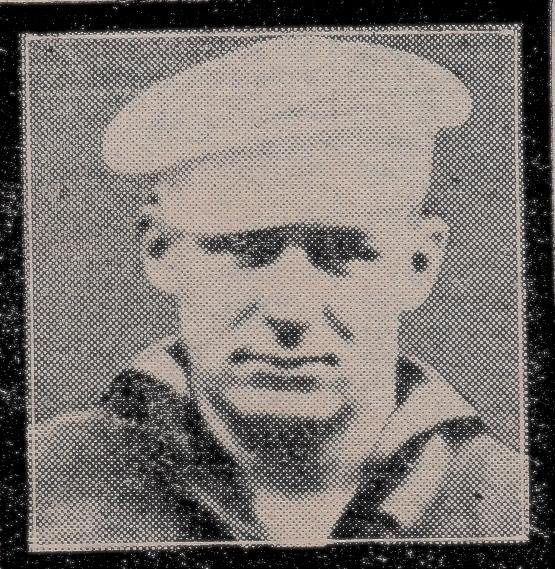

When you ask those familiar with the word “What was the world’s greatest airship disaster?” the vast majority of answers will probably be the horrendous explosion of the Hindenburg at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey on the evening of May 6, 1937. Out of the total number of 97 passengers and crew on board, 35 were killed along with one member of the ground crew. Anyone who has seen the famous newsreel footage of the Hindenburg going up in flames and crashing to the ground find it hard to forget. Nor can they forget radio announcer Herbert Morrison’s emotional cry of “Oh, the humanity!” as he witnessed the airship’s devastating conflagration. As memorable as the Hindenburg disaster was, it was not the world’s greatest airship disaster. That unfortunate distinction belongs to the all but forgotten US Navy airship, the USS Akron, nearly 4 years earlier. Ninety years ago, within the first hour of Tuesday morning, April 4, 1933, off the coast of New Jersey, the Akron went down into the Atlantic Ocean. It lost 73 of its 76 crew and passengers. Also perishing were two sailors who were attempting to rescue the survivors of the doomed airship. The “blimps” that can be seen flying over sporting events today are non-rigid airships. Typically the only solid parts on them are the passenger car (gondola) and the tail fins. Both the Hindenburg and the Akron were rigid airships. They had an outer structural framework that maintains the shape and carries all structural loads. The major difference between the Hindenburg and the Akron was the lifting gas. The Hindenburg used hydrogen. It has a high lifting capacity and was ready available but, as the Hindenburg proved in 1937, it is also highly flammable. The Akron used helium gas. It has almost the same lifting capacity as hydrogen and is not flammable, but is rare and relatively expensive. The Akron was the first of a class of two 6,500,000 cubic foot rigid airship built for the US Navy. Construction began in October 1929 by the Goodyear-Zeppelin Company at the Goodyear Airdock in Akron, Ohio. The USS Akron (ZRS-4) was christened on August 8, 1931, by first lady Lou Hoover, the wife of President Herbert Hoover. It was 785 feet long, about 20 feet shorter than the Hindenburg. It had a cruising speed of 55 knots (63 mph) and a maximum speed of 69 knots (79 mph). The USS Akron was a “flying aircraft carrier.” The heart of the ship, and said to be “her sole reason for existing,” was its airplane hangar and retrieval system. In May 1932, the Akron first tested its in-flight handling of the F9C Sparrowhawk, launching and capturing the small plane from its “trapeze”. This light biplane fighter was an example of a parasite fighter, a small airplane designed to be deployed from a larger aircraft such as an airship or bomber. The Akron could nominally hold five of the F9C Sparrowhawk, but practically it was limited to three. On the evening of April 3, 1933, the USS Akron departed the Lakehurst Naval Station at 7:28 p.m. on a mission to calibrate radio direction finding equipment along the coast of New England. A few hours after taking off it encountered unexpected severe weather just after crossing the east coast of New Jersey. The weather did not improve when the airship passed over Barnegat Light, New Jersey. Wind gusts of terrific force struck the airship's massive airframe. Around 12:30 a.m. on April 4, the Akron was caught by an updraft, which was followed almost immediately by a downdraft. Ultimately a violent gust tore away its lower rudder cables leaving the nose of the airship tilted upward between 12 degrees and 25 degrees. The crew was unaware of how close the tail of the airship was to the ocean surface because of its "nose up” position and the altitude indication was inaccurate. In that precarious position, and with the control gondola hundreds of feet high, her tail struck the ocean and its lower fin was torn off. The Akron then rapidly broke up and sank in the stormy Atlantic. Most of the 73 casualties met their death by drowning and hypothermia. Shockingly, the crew of the USS Akron had not been issued life jackets, and there had been no time to deploy the airship's one and only rubber life raft. The safety gear had been transferred to another airship and had not been replaced. The crash killed VIP passengers Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics who was often referred to as the "Father of Naval Aviation"; and Commander Fred T. Berry, the commanding officer of Naval Air Station at Lakehurst and its Rigid Airship Training & Experimental Squadron. The two were aboard the flight as observers. Another passenger on the dirigible that lost his life was Lt. Col. Alfred F. Masury of the US Army Reserve. Masury was vice president and chief engineer of the Mack Truck Company and was said to be “a fan of rigid airships.” It has been speculated that the Akron’s commanding officer, Captain Frank C. McCord may have commenced and continued the flight in the bad weather “in an attempt to impress them.” Capt. McCord also perished in the crash. Losing such leading proponents of rigid airships sounded the death knell of the US Navy’s program. President Franklin D. Roosevelt commented afterward, "The loss of the Akron with its crew of gallant officers and men is a national disaster. I grieve with the Nation and especially with the wives and families of the men who were lost. Ships can be replaced, but the Nation can ill afford to lose such men as Rear Admiral William A. Moffett and his shipmates who died with him upholding to the end the finest traditions of the United States Navy.” Of the 76 passengers and crew there were only three survivors: the USS Akron’s executive officer, and second in command, Lieutenant Commander Herbert V. Wiley; Boatswain's Mate Second Class Richard E. Deal, and Aviation Metalsmith Second Class Moody E. Erwin. In July 1934, Lieutenant Commander C. E. Rosendahl, after interviewing the survivors and examining the evidence, published the article “The Loss of the Akron.” In describing what happened on the dirigible in the early minutes of April 4,1933 he wrote, “Plunging suddenly into very turbulent air, the elevator man [controlling the altitude) reported the ship falling rapidly, the bow slightly down. His altimeter read 1,100 feet, he reported. Lieutenant Commander Wiley, second in command and a veteran of scores of scenes aloft in thousands of flying hours, jumped from his station near the directional control to the elevator man's assistance.” “The elevator man” Lt. Cdr. Herbert V. Wiley assisted was my uncle - 27 year-old Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Joseph J. Zimkus. On May 22, 1933, Lt. Cdr. Wiley gave testimony before a Joint Committee of the US Senate and House of Representatives. When asked who was in the control car of the USS Akron on that fateful morning of April 4, he answered, “Captain McCord, myself, officer of the deck, Lieutenant Redfield, elevator men Swidersky and Zimkus; and . . . the rudder man.” He was then asked if both Swidersky and Zimkus were “experienced men?” He replied, “Yes. Swidersky was the better elevator man. He was a better elevator man than Zimkus, but Zimkus has considerable experience. He was no rookie.” He was asked to explain “What makes a good elevator man?” He responded that it was one who “could keep the altitude with less motion of the ship than another man. That is, he reacts to his observation and instruments quicker than another.” When asked if he thought “a good enlisted elevator man is just as appropriately at that elevator control as an officer?” “Better, sir.” Wiley answered. He then explained its “because he gets some experience, and the training is considerable . . . We hold schools of instruction for the men . . . and try to give them enough of the background and knowledge of these things so that they can act intelligently and know what is happening. I think all of our elevator men without question were thoroughly conversant with all those things.” “You are perfectly satisfied with the system of having an enlisted man on the elevator wheel and rudder wheel?” he was asked. “Yes, sir.” was Wiley’s reply. Shortly before the crash, the Akron was flying blind because its radio had unusually heavy static brought on by the storm. "As they passed over the coast,” Lynwood Mark Rhodes in a 1966 American Legion Magazine article wrote, “elevator man Joe Zimkus saw lights below stretching away like a gleaming necklace toward the north. The problem was to identify them. Rapid changes in course had made it difficult to get an exact position fix. Were they from Atlantic City - or Coney Island? If Coney Island, that meant the Empire State Building loomed ahead somewhere in the shapeless, churning fog.” Rhodes went on to say,“Jagged streaks of lightening crinkles the control car walls when, pitching and tossing, first up, then down, the Akron hit storm center in a few minutes later. Zimkus had had considerable experience in such storms but it took all his strength just to hold the wheel steady. Suddenly violent turbulence hit the ship. The wheel spun from his grip, out of control, its handles racing like the hands of a clock gone berserk. ‘The ship’s falling!’ Zimkus yelled. [Coxswain]Toney Swidersky, standing behind him grabs hold of one of the spokes, bracing himself as best as he could. [Lt. Cdr.] Wiley dashed from across the car to help. . .” Within minutes all were in the ocean. “Water rushed through the open port window of the control car, which was listing to starboard,” wrote John Toland in his article on the Akron in the 1961 book Early Air Pioneers; 1865-1935. “The torrent picked up Wiley and carried him out the starboard window. He felt a mass of rubberized fabric on top of him and knew that he was being dragged down with the ship. He swam under water until his lungs seemed about to burst. Then he surfaced. Lightning flashed and, in the brief glow, he saw the dirigible, her bow pointed in the air, drifting away.” At 12:55 a.m., the now unconscious Lt. Cdr. Wiley was pulled from the water. The body of Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Joseph Zimkus was never found. Soon after her loss, Navy divers located the Akron’s wreckage about a hundred feet below the ocean surface east of Atlantic City, New Jersey. In June 2002, the research submarine NR-1 revisited the airship's crash site, where much of her collapsed framework remained somewhat visible in the murky water of the Continental Shelf. My Uncle Joe was born on June 10, 1905, in Stamford, Connecticut. He was the oldest of seven children to survive to adulthood of Lithuanian and Polish immigrants, Frank and Dominica Zimkus. He was not quite 11 years old when my father, Edward W. Zimkus, was born. Eddie, as dad was called, idolized his older brother Joe. Young Joe was apparently not much of a student. An article on him in the Stamford Advocate newspaper after the Akron disaster states that Joe enlisted in the Navy in 1920 “soon after running away from Rogers school in Stamford. His stature was greater that his years, and he was accepted.” (I attended the same Rogers Junior High School as a 9th grader the school year before my family moved to Ohio in the summer of 1964.) The 1920 US Census, taken on January 20 of that year, lists Joe Zimkus as being 14 and employed as a “bell boy” at a hotel in Stamford. By December 26, 1920, Joe, now 15, was in the US Navy. On that day, navy records show that he was admitted as a patient to the US Navy Hospital in Hampton Roads, Virginia with the notation, “Fracture simple left clavicle (fall).” Prior to his duty on the USS Akron, Joe was assigned to the USS Mahan (DD-102), a Wicket-Class destroyer that was converted to a light minelayer on July 17, 1920. In 1930, Joe married Naomi Miller. I don’t know much about my Aunt Naomi. I do know that she and Joe were married in Philadelphia, and that she was born in Pennsylvania. Census records state that Naomi was 12 years older than Joe. Joe Zimkus was counted twice in the 1930 US Census. On April 5, 1930, Joe, age 25, is listed as living with Naomi, age 37, at 128 Ninth Street in Philadelphia. The “head of house” is Joe’s “brother-in-law” Joseph Nelson. Ten days later, on April 15, 1930, Joe Zimkus is recorded again. His “street address” for this entry is the “USS Mahan - Navy Yard Philadelphia PA.” Uncle Joe is said to have “joined the Akron crew when the dirigible was commissioned.” That would put it in the summer of 1931. In April 1933, at the time of the Akron disaster, Joe and Naomi Zimkus were living in Whitesville, New Jersey about 5 miles from the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst. On April 6, 1933, two days after the disaster, The Western Star, the Lebanon, Ohio weekly newspaper, had a front page article whose headline read “Nation Shocked by Akron Crash.” The article recalled that on October 16, 1931, “Thousand of residence of the Miami Valley” watched “the ill-fated Akron, queen of the skies and pride of the Navy’s air service” fly over on its final test cruise. “Residents of Lebanon were able to secure a plain view of the Akron for several minutes as she appeared and gradually faded from sight in the western sky. Students in the local schools were given a brief recess in order to obtain a glimpse of the giant dirigible.” In 1948, back in Stamford, Connecticut, Ed Zimkus and his wife of three years, Betty, were expecting their second child. If it was to be a boy, Ed wanted to name it after his long lost big brother. That year, however, a cousin of Ed’s, who lived about 10 miles away, had a son and named him Joseph Zimkus. That infant, however, was not named after Ed’s brother Joe. To avoid confusion, when a boy was born in early March 1949, Ed and Betty Zimkus decided to still name the child after Joe but reversed the order of his first and middle names. That’s how I became John Joseph Zimkus. PHOTOS 1 The USS Akron (above) 2 A portion of the group photo of the crew of the USS Akron. Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Joseph Zimkus is believed to be the sailor on the floor in the middle. 3 A newspaper photo of Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Joseph Zimkus published after the disaster. 4 Uncle Joe’s US Navy duffle bag and footlocker, which are in my possession.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorVarious staff and volunteer writers. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Email: [email protected]

Wchs Office/Harmon MuseumTues - Sat: 10am - 4pm

Year Round |

1795 BEEDLE cABINPhone for hours

Year Round |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed